View a PDF of this story and download a brief store expansion guide that helps you analyze growth opportunities if you want to expand.

Overcoming the Challenges That Come With Growing Your Business

In 1998, Jeremy Melnick made a risky life change. He left a lucrative career in commercial lending to go to work with his father running Gordon’s Ace Hardware in Chicago.

At the time, the single-store operation was doing well for his dad, but Melnick knew that if he wanted a career in the family business, Gordon’s Ace would have to expand.

“My No. 1 goal was growth,” he says.

This need for growth motivated the Melnicks to open a second urban store in 2005, and begin a trialand- error journey that would propel the business to further expansion and even greater success.

The Melnicks found a location, hired new employees and filled the second store with merchandise. But what Melnick quickly discovered— despite help from other retailers and his co-op—was how much he didn’t know about what he was doing.

“We learned from the mistakes,” he says.

Expanding a business comes with many challenges, as retailers who have done it know well—and running a new second location, adding even more stores or making significant expansions within an existing store require careful thought and consideration. Assistance from a co-op or distributor and the input of other retailers can help mitigate failures, but some lessons have to be learned on the job.

In this article, retailers talk about what they learned when growing their operations. They also offer advice for how to manage an existing store while adding on to a business, let go of directly overseeing day-to-day operations and develop new operational processes that work for a larger company.

Opening Store No. 2

Many retailers say the transition from owning one store to two is very different than growing a business to three or more locations.

One major challenge of opening a second store is that the retailer has to give up direct supervision of staff and operations, perhaps for the first time.

Andy Boerman, owner of Ithaca Agway True Value in Ithaca, New York, opened his second store in 2013. He works primarily at his first location. From the start, he couldn’t be involved in his new store’s day-to-day operations due to his responsibilities at the original store.

“It was very nerve wracking,” Boerman says. “My wife tells me I’m a control freak, and it was difficult to pass those reins on to the manager and to have confidence in the staff.”

The Melnicks went from one to two stores first, and then added more locations in rapid succession. They opened store No. 2 in 2005, and then bought four additional stores right before the recession went full force in 2008. They had to close one of the four purchased stores in 2009.

The first store was owner occupied, so opening the second location required getting used to less control of day-to-day operations and learning from mistakes.

“One to two is really difficult,” Melnick says. “You have to get used to not being able to be in two places at once.”

Opening that second store in 2005 was harder than transitioning to overseeing six, he says. “Definitely one to two is the biggest culture shock,” he says.

The reasons are that you’re inexperienced, and you have to learn as you go. “You didn’t know what you didn’t know,” he says.

Deciding to Grow

Choosing to expand a business may mean doing what makes sense to support a family or deciding to meet existing consumer demand in a market.

When Melnick planned to expand Gordon’s Ace to two locations, his goals were to support more than one family and build a career, achieving a lifestyle that didn’t require him to be at a store from open to close.

He advises that every retailer expand, but not stop at growing to a second location. You gain efficiencies by owning more than two locations, and adding on after two isn’t as difficult as that first big step from one to two stores.

“Don’t believe all the hype. It’s going to be hard, but you need to do it,” Melnick says. “Don’t stop at two. If you’re going to plan to expand, think longer term. The bigger you get, the more infrastructure you can have, and the easier it actually is.”

Gordon’s Ace now has eight stores, three of which the company bought within about two years of the second store opening. Such quick growth wasn’t the plan. “The goal was to get from one to two and digest that,” he says.

Then an owner of four nearby Ace stores offered to sell his business to the Melnicks, and Gordon’s Ace went from two stores to six.

“Were we ready for it? Honestly, no,” Melnick says. “But it was an opportunity that made sense, so we rolled up our sleeves and did it.”

For the owners of Alpha Building Center in Shipshewana, Indiana, expansion came as a natural response to consumer demand.

“We needed more store here to service the market,” retail store manager Trevor Nice says. “We were losing sales to the market we were already in because we didn’t have the right products or product mix.”

The business, which is primarily a lumberyard, had a hardware store that was too small to stock many of the products customers in the area were requesting. The 4,800-square-foot location couldn’t carry a broad mix or multiple brands and styles of tools. But the opportunity to sell far more product was there; the closest big-box home improvement store was 15 miles away.

The store’s co-op, Do it Best, did a market analysis, which showed that the area could support a much larger store. The owners then chose to add on, more than tripling the store size and expanding categories, such as housewares, Nice says. The renovations were completed in May 2013.

Boerman also grew his business to fill what he saw as a market gap. He opened his second location in Ithaca after a paint store closed. He knew he could fill the paint store void. Additionally, sales at his first store showed he had space to expand categories, such as hardware and outdoor work wear and footwear. He also wanted a location with wider aisles that would be easier to shop, Boerman says. That style of store appeals more to younger customers, who he is working to engage, he says.

Trial and Error

Learning by trial and error has been part of growing both Gordon’s Ace and Alpha Building Center.

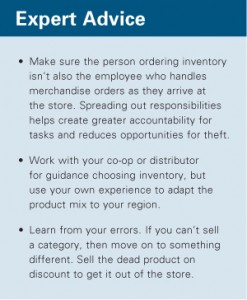

For example, Melnick didn’t realize how few systems were in place for employees to follow to run his second store. He was used to overseeing all of the operations daily in the original store, so he didn’t have written rules or procedures for processes, such as ordering product, training employees and spreading out duties.

Those documented procedures were needed for the store to operate well without the Melnicks’ perpetual oversight. The lack of checks and balances resulted in problems, such as employee theft.

“I wish we’d had more systems in place before expansion, rather than as a fire drill post-expansion,” Melnick says.

Because of the theft problems, he had to replace some employees and look into how the staff was doing returns at POS and how inventory was being managed. He also developed rules so multiple people were handling store closing and opening and not one single person was doing a procedure from start to finish, he says. The Melnicks fixed the operational problems and moved forward.

“We’ve corrected them and try to always improve,” Melnick says.

The lessons you learn from expanding an existing store look a little different from adding a location.

Since Alpha Building Center was already an established business, choosing the product selection was the primary area where the staff learned by trial and error, Nice says. For the most part, the expanded product array has been popular. However, some haven’t worked. For instance, the store tried to make a push to sell home organization products, such as shelves and closet organizers.

“That’s been kind of a dead one for us,” Nice says.

Like the Melnicks, the staff at Alpha Building Center has learned from mistakes and adapted.

Finding the Right Location

Choosing a location for a new store or deciding where to buy a business is of paramount importance to business success.

The Melnicks knew when they bought the group of four urban Chicago stores that one of them would likely have to be closed. That downtown store was located in a business district that didn’t have residential neighborhoods nearby and that emptied of people in the evenings and on weekends. The location didn’t work. The store continued to underperform, so the Melnicks closed it.

Other locations have worked well because they are densely populated residential areas, and the stores are close enough to each other to share employees and drop-ship efficiencies and yet each serves a different customer base, Melnick says. The 2008 purchase of the four urban stores was mostly successful. The locations were close enough to the two existing Gordon’s Ace stores for operational efficiencies.

“They were the four closest Ace stores within a 6-mile radius in downtown Chicago. It just seemed to make sense,” Melnick says

Proximity was also important to Adam Barden, owner of Frankenmuth True Value in Frankenmuth, Michigan, and Vassar True Value in Vassar, Michigan.

The 10-minute drive between the stores “provides us a lot of operational advantages,” Barden says.

The 10-minute drive between the stores “provides us a lot of operational advantages,” Barden says.

His stores can share merchandise or employees when needed, and offer services, such as party tent and table rentals, without storing rental items at both locations. He also chose a building near a Kroger store so he can capitalize on existing shopper traffic.

Boerman with Ithaca Agway relied heavily on True Value and the co-op’s demographic research and financial models to help him choose his second store’s size and location. He couldn’t find a property for sale that fit his price range, so he chose to negotiate with a landlord for the 22,000 square feet of retail space he decided he needed.

Hiring the Right People

Hiring the right people to operate a new location is key, but moving existing employees to new stores can reduce the risks of having to trust all new workers.

Melnick recommends promoting alreadytrusted employees, and moving workers from your successful existing enterprise to the new location instead of “back filling” with new hires. He prefers to hire new people for entry-level jobs.

He reaped the benefits of developing his existing staff. “We had a relationship, rapport,” he says.

His business has grown stronger overall because he promoted from within and retained some talented staffers from stores he bought, Melnick says. Keeping an eye out for exceptional workers at a store you buy is important, he says.

When he bought existing stores, he gained insight into back-office policies as well as employees who were used to following those policies and working with an absent owner.

“Those are the same three folks I have today, eight years later. That helped us because we could learn from what they were already doing,” Melnick says.

Boerman was also able to promote some of Ithaca Agway’s employees and transfer them to his new location.

Moving employees who have worked for you awhile spreads the business’s existing culture, he says. “They already knew my management philosophy and they were able to convey that to the rest of the staff,” he says.

Moving employees who have worked for you awhile spreads the business’s existing culture, he says. “They already knew my management philosophy and they were able to convey that to the rest of the staff,” he says.

However, Boerman had to find a general manager for his second location, and he consulted people he trusted to help him. He ended up feeling confident in his general manager hire because he knew other people who had worked with her and respected her.

“I’m a firm believer in being able to use word of mouth in finding recommendations from people you trust that have had experience with working with that person,” Boerman says.

Overseeing Staff From a Distance

One of the difficulties of moving from operating one location to managing multiple stores is learning to let go of making day-to-day decisions.

“You just had less control. Most of us, for lack of a better term, are control freaks,” Melnick says.

Establishing checks and balances for store procedures, such as ordering inventory, has helped build his confidence that his employees are operating his stores well without direct supervision.

“If you don’t trust your people, you can’t grow. You have to have some trust,” Melnick says.

Melnick and Boerman both can watch their stores’ surveillance video feeds on mobile devices, so they can always take a look at how things are going.

When he is working from his original location, Boerman watches video from his second store and looks at sales numbers multiple times a day to keep track of what’s happening. He also talks to the manager daily.

Boerman can view the surveillance videos on his cellphone and in his office. He installed the cameras “for security purposes, as well as peace of mind for myself to personally monitor how things are going,” he says. “It just made me feel more comfortable about not being able to be there. I could look at the cameras and know that people weren’t waiting at the checkout longer than they should have been, or wandering around the store without getting assistance.”

Barden, who opened Frankenmuth True Value in August, moved himself to the new store and entrusts the original store to employees who have worked for him for decades. “The staff here are all competent and they care about the business,” he says.

Barden, who opened Frankenmuth True Value in August, moved himself to the new store and entrusts the original store to employees who have worked for him for decades. “The staff here are all competent and they care about the business,” he says.

He eventually plans to divide his time evenly between the locations. In the meantime, he is comfortable with spending most of his time at the new store because he knows his employees will call him if they need him but will mostly manage on their own.

“The one thing that I had that was a big advantage was that our store in Vassar has been there for 35 years,” Barden says. “This store can pretty well run itself seamlessly without me being there.”

Managing Inventory

Inventory management is an area these retailers have learned about as they go. Finding a balance for what products go in what store was difficult at first for the Melnicks, especially before Gordon’s Ace had systems in place for ordering, buying and receiving. It was prior to thinking through those procedures that employee theft became a problem.

“I wish I had been more prepared from one to two stores,” Melnick says. “I think the biggest mistake, again, was inventory management.”

Keeping track of product outs, making sure drop-ship orders were correct and taking steps to avoid over buying product were difficult without written back office rules for managers to follow and direct

oversight from him and his father, he says. Replacing employees and establishing written procedures were necessary—and buying stores that already had good practices in place helped the Melnicks learn what to do better with the first two locations.

In contrast, Barden’s inventory management tasks have involved choosing the product mix and expecting to learn from his mistakes when it comes to inventory levels. His store is just months old, so he isn’t certain what’s ahead.

For choosing merchandise for the Frankenmuth store, Barden turned again to his co-op for help. He considered True Value’s recommendations planogram by planogram and also ordered items he knew were of regional interest.

He believes he already has a good idea of what products will sell well, but he will learn to manage inventory by occasionally ordering too much or not having enough product in stock. Among other reasons, he isn’t certain yet who his strongest customer base in Frankenmuth will be. “There’s going to be a learning curve,” he says.

He believes he already has a good idea of what products will sell well, but he will learn to manage inventory by occasionally ordering too much or not having enough product in stock. Among other reasons, he isn’t certain yet who his strongest customer base in Frankenmuth will be. “There’s going to be a learning curve,” he says.

At Alpha Building Center, existing employees chose inventory for an existing customer base, so any trial and error were on a small scale. The staff primarily expanded on already popular product categories when they opened the drastically larger salesfloor.

“You’re going from having a few miscellaneous items to creating a category and a destination for that type of product,” Nice says.

Hardware Retailing The Industry's Source for Insights and Information

Hardware Retailing The Industry's Source for Insights and Information