To view a PDF of this story, click here. To download a helpful inventory accuracy tool or to use an inventory calculator, which helps you determine the amount of lost sales due to out of stock inventory, click here.

By: Liz Lichtenberger llichtenberger@nrha.org and Jesse Carleton jcarleton@nrha.org.

Analyze Five Critical Parts of Your Inventory’s Life Cycle

In a perfect retail world, inventory moves in and out of your store in one continuous cycle. From the time product arrives on the truck to the time it leaves in a shopping bag and is time to reorder, you’ve maximized every inventory dollar and every inch of shelf space. Turns and GMROI are high; dead items low.

But sometimes that perfect cycle hits a snag, and it’s likely happened to anyone who has been in retail. Maybe, for example, you’ve ordered too much of a slow-moving item and it ends up sitting on the shelf for a long time. Or maybe your POS says you have six widgets on the shelf, and you can only find three. There are many places where the inventory cycle can break down, resulting in your business tying up valuable inventory dollars or wasting critical shelf space.

When the inventory management process hits a snag, how do you get it back on track? For some possible solutions, we turn to a group of the industry’s bright young leaders who addressed inventory management solutions as part of their business improvement projects with the North American Retail Hardware Association’s (NRHA) Retail Management Certification Program (RMCP).

Understanding how to make the inventory process run smoothly in your operation is an ongoing challenge, and it may look different for different types of retailers. But while these retailers and RMCP graduates received a final grade based on a predetermined set of criteria, how well you solve your inventory issues will be graded by higher profitability and customer satisfaction marks. If you fail, you will fall further behind the competition.

On the following pages, we’ll analyze the inventory management projects of five of these retailers. Each of them addresses a critical point where the inventory cycle can hit a snag, causing problems in the rest of the process. As you consider the solutions each retailer came up with to solve his or her operation’s inventory challenge, take a look at your own store. Are you facing some of the same challenges, and if so, how do you propose to fix them?

For resources beyond the pages of Hardware Retailing, go to TheRedT.com/inventory to learn how frequently you should check various inventory processes and to find a calculator that will help you determine the true cost of ineffective inventory management. Also see this month’s Trainer’s Toolbox (at nrha.org/FreeTraining) for two lessons that will help you teach employees the basics of the inventory cycle and what they can do to help keep inventory productive.

Setting the Right Order Points

Holmes Building Materials

Two locations in Louisiana

The Challenge

For years, Ben Canady and the rest of the team at Holmes Building Materials, which has locations in Baton Rouge and Denham Springs, Louisiana, was focused on growth.

In the meantime, inventory “kind of exploded a bit,” says Canady, assistant manager for the Baton Rouge location. “Sometimes we treated the salesfloor like a fancy warehouse.”

He says part of the issue was that they erred on the side of caution, ordering a little more product than needed. But too much inventory meant tying up cash, sometimes in slow-moving items. There was also no automated way to order, and the manual process led to even more over ordering. And other areas were under stocked, leading to frequent outs in key products.

The Solution

Canady decided to change the inventory control system from personnel-based to computer-based. He talked with store owner John Holmes, and the two set some goals, which included reducing the Baton Rouge store’s total inventory by 25 percent, without reducing any sales, and reducing customer-perceived outs by 50 percent.

Canady also took advantage of the store’s brand-new POS system, and looked to other employees for help, including a former merchandiser, Jason Mitchener, and Donna Dunnehoo, inventory specialist.

Canady’s first step was to go through products on the showfloor, then move into the assortments of lumber and moldings.

“Once the store is 100 percent through this, we will take a look at the numbers and make sure it’s not hindering sales,” he says. “Then, we’ll try this in our other location.”

The Process

Canady divided the store into 10 sections, knowing it was important to tackle the project a little at a time. The original goal was to complete a section every 30 days, although he and Holmes agreed to extend the timetable when needed. After finalizing his project in the fall of 2014, when he participated in the RMCP class, he completed the first section in January 2015, and the team is taking each section one by one.

In doing the checks, they walked the store and thoroughly scanned each section for empty hooks or shelf space. They also used a handheld scanner to check for customer-perceived outs, and then compared that report to what the POS system said was on hand. Next, they were able to stock the shelves with items they had in stock, as well as correct inventory counts, based on shrinkage and invoice errors.

“After all were identified, we categorized items as either ‘true outs,’ stocking errors, shrinkage or invoice errors,” Canady says. “We felt like the more true outs we had in our report, the better our team was doing at stocking and selling.”

The new POS system doesn’t yet have a solid sales history; until it does, they manually adjust the min/max quantities. “Eventually, we want the system at a point where the store will receive product to maintain an appropriate stock level.”

One hurdle, and a reason for the extended timetable, was the new POS software. While it’s helpful, it takes time to learn, Canady says. He says Mitchener, who’s more familiar with the system, was a great help in utilizing it fully.

And of course, he didn’t want customer service to suffer. “Taking care of customers is the most important thing.”

The Results

Within the first six months, Canady saw a reduction in cost on purchase orders through his distributor, and a reduction in inventory levels for some products. He’s relied heavily on his employees and says feedback has been good.

They’ve reached their goal of reducing customer-perceived outs by 50 percent. The other goal is to reduce total inventory, without reducing sales, by 25 percent. Canady says the inventory reduction is currently at 15 percent, and he expects to reach 25 percent by the end of the year.

Best Practices for Receiving

Wilco

16 retail locations in Oregon and Washington

The Challenge

With 16 retail locations, Wilco sees plenty of product being shipped to the stores, stocked in back rooms and put on salesfloors. Store managers Stacia Motta and Amber Matchulat saw that, while there wasn’t a problem getting that freight to the back room, there was trouble getting the product from the back room to the salesfloor.

“The back room was packed full,” Motta says. “Getting that product on to the floor was a huge issue, due to the amount of time and people responsible for maintaining it while also helping customers.

“The freight coming in was getting put away that day; it was just working through that huge amount of backstock to keep the shelves full that was the problem,” she says.

The Solution

One part of the solution had been implemented a couple of years ago, when night stocking at the company’s three largest stores was switched to day stocking.

“The biggest issue with night stocking was that there was no manager at night,” Matchulat says.

An advantage, of course, was that no customers in the building meant stockers could work more quickly, rather than taking time to help customers. But day stocking meant there was a leader in place, and freight was worked right away.

The change from day to night stocking at those three stores was made about two years ago, Motta says.

The second part of the solution, which was implemented more recently, was to add a full-time stocking position at all but one of the operation’s retail locations. (The last location was too small to necessitate the new position, Motta says.)

The Process

Motta and Matchulat chose three Wilco stores to be the test locations for the new full-time stocking position, with the plan of testing out the new position from mid-August to mid- December of 2015. After that testing proved to be a success, they hired a new full-time stocker for all but one location, with the plan to also have one or two part-time stockers at some locations, as well as seasonal stockers when needed.

Motta and Matchulat say the full-time position has helped maintain efficiency throughout the store and warehouse. “If a manager isn’t there, the full-time stocker can take on that leadership role,” Motta says.

The two worked with Wilco’s central office to ensure the new stockers had the training they needed and that it was consistent across locations. They created sample stocking and push cycle schedules to illustrate the process.

Along with training, another challenge was finding full-time stockers who met all the qualifications for the job, and also had leadership experience.“We updated pay scales to make some of these positions more attractive,” says Motta.

Of course, support from management was necessary to ensure that adding the new position would help the company.

“Our managers are on board and coming to us with questions,” Motta says. “Our district managers are fully in the loop and have been involved since day one.”

The Results

Motta and Matchulat knew adding the stocking position was a good idea, as the pilot testing had proven. “We know it’s working; we have that proof it’s working,” says Matchulat.

At Wilco, the out-of-stock percentage has been required to be below 1 percent. Since the new stocking position was added, the percentage has been closer to 0.5 percent.

“My store even reached .18 percent at one point in January,” she says. “The new expectation is now less than 0.5 percent.”

“Seeing how low those numbers are getting really shows how well this new program is working,” Matchulat says. “It’s a lot of pressure on our stocking team to maintain those levels, but they are doing it well.”

Cycle Count Stock

Picton Home Hardware and Building Centre

One location in Picton, Ontario

The Challenge

In any store, there are a variety of factors that may influence inventory accuracy: shrinkage, inaccuracies in receiving, an occasional missed item at the cash register or merchandise in the wrong place in the store. Picton Home Hardware had an added challenge. In 2009, the company expanded the store from 15,000 square feet to a new 50,000-square-foot building. While the store had all the marks of a modern shopping experience, in the hustle to get it stocked, there was no thorough accounting of all the inventory. Previous inventory methods had been spotty: There was a year-end inventory process that

wasn’t well-suited to a large store; there was not an established practice of cycle counting; and multiple employees might be ordering for the same department. Four years into the new store, no one had done a complete inventory. Numbers in the POS didn’t match what was on the shelf, and the store owners discovered a substantial amount of unaccounted inventory dollars.

The Solution

Shutting down the busy store for a complete inventory was not possible. Instead, store manager Dwayne Gibson came up with a solution: cycle count 4-foot sections of the store over a period of several months.

During the process, each 4-foot section would get a location code that would be entered into the POS system so employees could easily find it in the future. Those location codes would also allow him to monitor sales per square foot. Gibson also set min/max levels for each item so ordering would be more structured and he could keep track of stock outs.

The Process

To make the counting most efficient and effective, Gibson used RF scanners to count each item, and he decided to get all of the employees involved in the process. Throughout the day, any employee could grab a scanner to count a 4-foot section of the store. Gibson created a variance report from that count and addressed missing items. He assigned a second person to recount the section, and sometimes a third or fourth person, depending on the extent of the variance. Having multiple people count helped account for human error and established a solid foundation for future counts.

“We created a system to count a 4-foot section, give it a location, then have a second person count it to verify the number,” he says. “This has become something we do on a regular basis now.”

After finishing the count for each section, Gibson reviewed and altered min/max order points for each item, which, with twice a week delivery, he anticipated would reduce the amount of overstock needed.

The Results

It took a full year to complete the initial inventory, but it only took a couple of months to see real results.

“For a two-month period, we projected we would recover about $200,000 worth of inventory,” he says, “and we ended up accounting for $650,000. That’s when we were able to get all of the staff excited about doing this project, because they could see the results from their work.”

By the end of the year, Gibson was already seeing an improvement in inventory turns and a decrease in excess stock.

“We found a lot of orphan items; we were able to free up a lot of dead stock and free up dollars for more inventory,” he says. That all added money back to the bottom line and improved his customer service due to fewer out of stocks and less wait time trying to find a requested product.

Today, cycle counting is part of Picton Home Hardware’s daily culture. “The entire store will get counted twice a year,” he says. Gibson has posted a map of the store showing what sections need to be counted. When employees have a free moment, they’ll grab the scanner and inventory a 4-foot section.

Shooting the Outs

McLendon Hardware

Seven locations in Washington

The Challenge

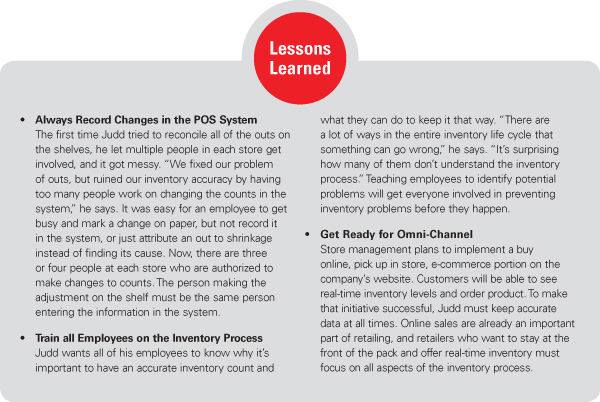

In 2013, Steve Judd, corporate inventory manager for McLendon Hardware, was reviewing sales increases for the company’s seven stores. The store in Woodinville, Washington, posted a sales increase well above 8 percent for the year, while the other stores were below 4 percent. A walk through the Woodinville store revealed few empty hooks, and an inventory accuracy report showed the store was about 75 percent accurate, while several of the other stores were below 50 percent accuracy.

“The manager of that store used to work for a national competitor, where they shot their outs all the time. You could tell a difference, because they were more in-stock and more organized than any of our other stores,” says Judd.

Shooting the outs, or using an RF gun to scan bin tags on empty shelves, was something the company hadn’t done for nearly 10 years. In addition to having no company-wide process for identifying missing inventory, there was no cycle counting and no way to find shrinkage until the year-end physical inventory. It was time to change, says Judd.

The Solution

“Our goal was to have at least 75-percent accuracy across all of our stores in the first year,” says Judd. To get there, Judd proposed training employees to shoot outs, and then fix problems as they found them. To be effective long term, identifying missing merchandise would need to be a regular process. Judd decided to standardize that process for all stores and establish preventative measures against future outs.

The Process

The fastest way to grasp how many empty spots were on the shelves was to use an RF gun and scan bar codes of every place where there was a bin tag but no product. Judd involved every employee in the initial shooting of outs. After they finished shooting the store, Judd used those lists (which he compared to quantity lists in his POS system) to get an overall accuracy report for the store and to create individual reports for each department. With their list in hand, each department head reconciled out items and filled in the missing inventory.

While his initial project may have been a quick fix to get product back on the shelf, today, nearly two years later, Judd has refined the process to be a part of the store’s daily life.

Judd has employees shooting outs on a daily basis, and he travels to each of the company’s seven stores twice a month to do his own audit. In addition to identifying outs, Judd has instituted several preventative measures, the biggest being aisle maintenance. Every employee has certain aisles assigned to them, and they are responsible for maintaining that aisle, including cleaning and down stocking. All managers conduct monthly audits of each aisle and submit a report to Judd.

The Results

By knowing outs in the store on a regular basis, Judd and his team can quickly identify and correct the problems that caused those outs. While he reached his goal of having average inventory accuracy rates at 75 percent or above, other results have been noticeable, too.

The most noticeable difference was in shrinkage rates, which are now much lower than before Judd started shooting outs. In years past, each store’s management team only calculated shrinkage once a year after the physical inventory. “Now, we can determine shrink on a daily basis. When we catch theft right away, we can try to control it,” says Judd.

Other key performance indicators have also been up in all stores. “Average transaction size went up 7.4 percent in 2014, the first year we started counting outs,” says Judd. “Inventory turns increased to 4.5 from 4.0.” While he admits that a lot of factors influence these numbers, he believes having full bins and hooks have a ripple effect through the entire store.

Purge Slow-Moving Inventory

Mayer Paint & Hardware

One location in New York

The Challenge

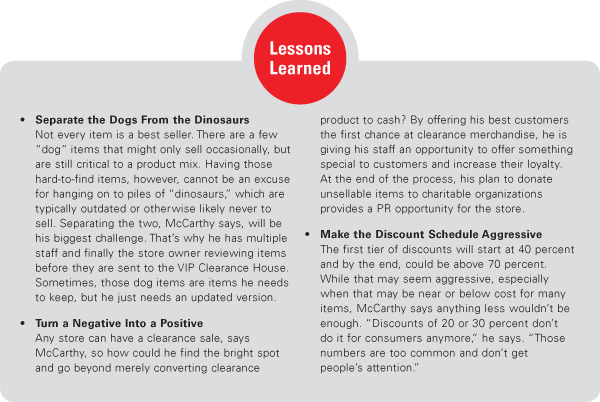

Mayer Paint and Hardware, like many small retail establishments that have been in business for many decades, is known for being a small store with the offerings of a big store, as well as many hard-to-find items. In fact, owner Tom Green has made such good use of his 5,000-square-foot store that the store posts annual sales well above the industry average. But that strength is also a weakness. Being the store that had everything sometimes meant they were keeping a lot of inventory that wasn’t productive, and having too much stagnant inventory was eating up a lot of valuable space and cash. While the store hosted an occasional clearance sale, there was still a lot that got missed. “We never had a regular process to address unproductive inventory,” says store manager Dennis McCarthy. “If stuff started to pile up, we might move it to a discount table. Sometimes we ended up discarding what didn’t sell or sending it back to overstock areas, and we didn’t always evaluate inventory files to catch all of the dead items.”

The Solution

McCarthy created a process that would identify unproductive inventory items and convert them into cash. Rather than collecting everything for a single sales event, McCarthy’s plan is to use several channels for gradually clearing merchandise, at an increasing discount schedule. The centerpiece of the process is the “VIP Clearance House,” a showroom of select clearance items. Select customers will have exclusive access to this merchandise.

Goals

While McCarthy has already established a solution, as one of the most recent graduates from RMCP, the execution is still in its infancy. But after taking a few customers through the VIP Clearance House, response has been positive.

In addition to clearing unproductive merchandise from the shelves, McCarthy hopes to find a spot for more new items.

While he hasn’t determined yet if the VIP House will be an ongoing feature of the store once he clears out the current glut of dead inventory, he does plan to make formal merchandise evaluation an ongoing process. “Eventually I want to get to the point where we’re evaluating our inventory a section at a time, and where it’s a regular process,” he says. “I think we can make our product mix more efficient by getting to that level.”

The Process

McCarthy’s plan starts with a report generated by his POS software that identifies all X items that have not been sold in the past year. Staff will pull those items off the shelf or out of the backroom and place them in totes.

Next, a manager and finally the store owner will review all items in the totes and determine which items should be cleared and which need to stay in stock because, even though they were slow movers, they are essential to a complete hardware mix.

As clearance items are identified, McCarthy has several channels for selling them. Next to the store is an empty house which will serve as the VIP Clearance House. The House contains select clearance items (selected by a manager), priced at a 40-percent discount or more, for the store’s VIP customers. Who is a VIP customer? McCarthy empowers each employee to select loyal customers and invite them to the House. He’ll also utilize his co-op’s loyalty program to identify VIP customers and also send invites to the House in monthly statements to commercial customers.

Merchandise that sits in the House for about a month without selling moves to an in-store clearance area. Then, McCarthy will hold two sidewalk sales. This will be the final attempt to sell clearance items in store before McCarthy utilizes online channels, such as Amazon and eBay, to sell remaining clearance merchandise. Items that remain unsold will be donated to local charitable organizations or discarded

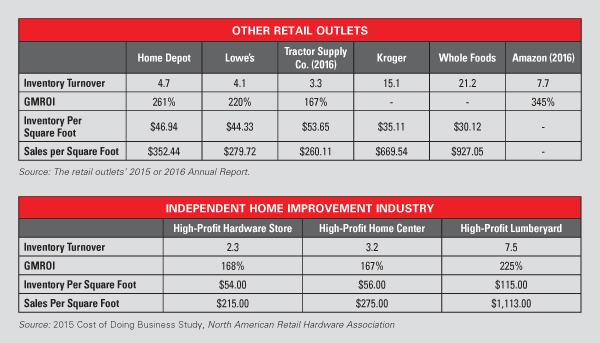

Four Key Inventory Productivity Figures

Definitions

• Inventory Turnover

Cost of Goods Sold/Inventory

Normally a high turnover rate means good inventory management, while slower turnover indicates too much inventory for the sales it generates. Some retailers also look at Sales to Inventory, which is another way to measure turns. It provides an indication of the amount of merchandise on hand relative to the amount of sales volume it generates. Sales to Inventory is calculated by taking Net Sales divided by Inventory.

• Gross Margin Return on Inventory (GMROI)

Gross Margin Inventory X 100

This ratio measures the amount of gross margin dollars generated by each dollar tied up in inventory. GMROI allows managers to evaluate products and departments that have varying gross margins and inventory investment requirements. It helps retailers compare high-turn/lowmargin lines against slower-moving/high-profit ones.

• Inventory Per Square Foot

Inventory/Square Feet of Selling Area

Stores that stock more inventory per square foot typically generate higher sales. However, managers also need to consider other inventory measurements, such as turns.

• Sales Per Square Foot

Net Sales/Square Feet of Selling Area

This classic measurement remains one of the most important gauges of a store’s productivity.

Key Takeaways

• Compared to other businesses, independent home improvement stores are underperforming in metrics related to inventory productivity on average. They are also stocking more inventory per square foot than competitors.

• Grocery stores have three to four times higher inventory turns and productivity than the home improvement industry, with fewer dollars tied up in inventory per square foot. They also produce two to three times more in sales per square foot. Amazon ranks between the two.

• Since Whole Foods has smaller stores with similar layouts, it has incrementally higher inventory productivity ratios than Kroger. Kroger’s metrics include a variety of store formats, such as pharmacies and fuel centers, since Kroger Co. encompasses a wide array of store types.

• The differences between typical and high-profit stores, in terms of inventory productivity, are dramatic. Typical hardware stores generate $1.30 in gross margin for each dollar invested in inventory (GMROI) compared to $1.68 for high-profit hardware stores. For home centers it’s the same scenario, with typical home centers generating $1.44 in GMROI to $1.67 at high-profit stores. For lumber and building materials outlets the gap widens, with typical LBMs generating $1.63 in GRMOI compared to $2.25 for the highly efficient, high-profit operators.

Hardware Retailing The Industry's Source for Insights and Information

Hardware Retailing The Industry's Source for Insights and Information